“A resilient supply chain is as much about being able to fight recovery battles in the here and now, as about being able to secure a strategic advantage in times of crisis that competitors won’t have the ability to replicate.”

-David Irvine, MD, Siecap

Where To Put Your Focus

The high-risk reliance of the global supply chain on a few critical nodes, single sources of supply, tiny tier 3 producers or rational jurisdictional behaviour has been significantly elevated in the public consciousness as a direct consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet warnings relating to the fragility of the global supply chain were apparent long before January 2020. The 2011 Japan earthquake and its disruption to tier 2 automotive suppliers had ramifications all the way to Detroit and Cologne. Cyclone Debbie in March 2017 significantly impacted coal production in the Bowen basin and drove a significant and lasting spike in metallurgical coal prices.

The 2019 disruptions by the Iranian government to the tanker trades in the Gulf drove a corresponding spike in crude oil prices. Perhaps these were not of the scale of COVID-19, but each in its own way flagged how exposed a global trade-based economy such as ours is.

The collective failure to plan for a major global disruption event, and more specifically how to structure supply chains to respond, has been a failure of emphasis for many. This now demands the need for change, by giving greater weight to the design of resilient supply chains.

Refocusing on supply chain resilience will serve not just as a key risk management strategy but will assist organisations in meeting their legislated obligations in other business critical areas.

A live example of this is the 2018 Modern Slavery Bill and the approaching September 2020 deadline for organisations to provide their initial set of Modern Slavery Statements indicating the way they will address modern slavery risks in their supply chains and operations.

“COVID 19 is proving to be the black swan event that is demanding organisations reconsider and reengineer their supply chains for greater resilience.”

-David Irvine, MD, Siecap

The 2020 Supply Chain Landscape

Our supply chain operations have evolved significantly over the last thirty years. First, as tariff barriers were eliminated, then following the 2001 admission of China to the WTO, and more recently the increasing series of bilateral regional trade agreements that have been put in place with Australia’s major trading partners. These have transformed the way we source, manufacture and deliver. These impacts have been most evident within manufacturing, with a sector decline from 14% of GDP in 1990 to around 6% today. This decline has been driven by businesses moving operations offshore or shifting to global sourcing. Parallel to these shifts, the role of the supply chain has become more critical. In addition, rapid improvements in communication and technology enable the provision of the support needed for the further incorporation of emerging sourcing points.

However, this changing environment brings added risks arising from the need to accommodate international jurisdictional complexity and counter-seasonal challenges in the context of our sub-scale market and global economic pressures. While it is true that businesses have in many ways adapted to these challenges, it has largely been a response borne of short-term necessity and often developed through a narrow prism of internal need. After all, who had the time to sit back and take a whole-of-system view of how the risks would combine and magnify exponentially?

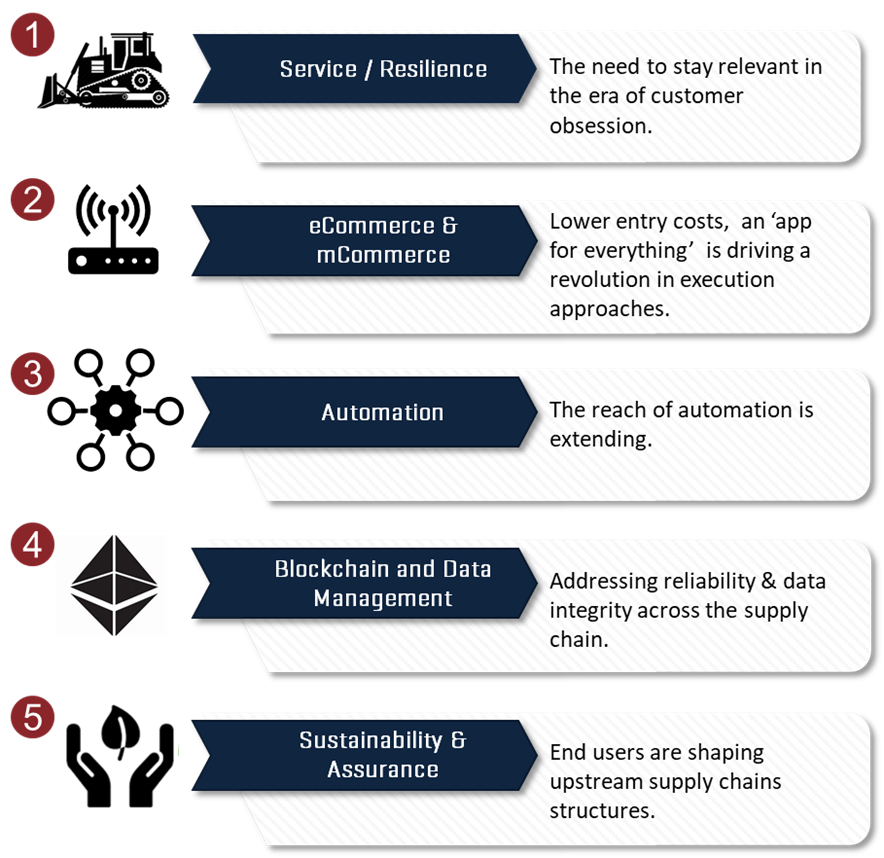

In response to our own observations and what our clients are relaying, Siecap has formed a view of five trends that demand focus, given their potential to further shape supply chains over the next five to ten years. Recent circumstances have reinforced the relevance of these trends and the elevated urgency to develop appropriate strategies:

- Service and Resilience

- Ecommerce and M-Commerce

- Automation

- Blockchain, Data Management & Analytics

- Sustainability and Assurance

5 Supply Chain Trends

The need for visibility within the supply chain

The common thread between the now heightened requirement for Service/Resilience (1) and Sustainability & Assurance (5) is the need for visibility across the layers of an organisation’s supply chain.

This means knowing; –

- where goods and materials are coming from,

- who is making them,

- who they in turn are reliant upon, and

- what conditions are associated with their production?

These are all core questions needing answers. Indeed, recent events have exposed how little is understood about these questions within the global supply chain. The focus on low-cost sourcing has gone hand-in-hand with a limited understanding of supply chain risks. This is illustrated in the findings of a worldwide survey conducted by freight company Geodis. It indicated that only 6% of companies have full visibility of their supply chains despite their high dependency on global suppliers.

In 2019 Siecap worked closely with Australia’s leading Agricultural Chemical company to develop a solution for a comprehensive global visibility platform. At its core, this platform will provide the capability of tracking, in near real time flows, the supply and regulatory risks associated with the company’s domestic manufacturing and distribution business.

Modern Slavery

Responses to these five trends necessitate additional outlays, but consumers, it appears, are prepared to bear the costs, particularly regarding sustainability and assurance. MIT researchers have found that consumers are willing to pay 2% to 10% more for products that are associated with greater supply chain transparency. This is significant, particularly when failure to achieve such transparency comes with a devastating impact on the most vulnerable participants or communities connected to global supply chains.

For example:

- the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh killed over 1,100 people and severely affected mass market clothing retailers;

- the use of Rohingya slave labour in the Thai seafood industry and the deforestation and destruction of habitat in Malaysia and Indonesia reflect negatively on the moral integrity of global supply chains.

The legislative response to such horrific events and practices has seen the Modern Slavery Act 2018 being passed in Australia. It is designed to cast a spotlight on these practices and drive their elimination.

Essentially, a company must now describe:

- its structure, operations and supply chains;

- the potential modern slavery risks in its operations and supply chains; and

- the actions taken to address the risks, including due diligence and remediation

The common thread and first step for creating an assured and resilient supply chain is understanding an organisation’s operation. This can be achieved through increasing visibility and using the resultant understanding to determine risk exposure.

COVID-19

The effects in heightening focus

The effects of virus containment measures have led to industrial production in China declining by 13.5%. According to Dun & Bradstreet, this has directly impacted five million companies globally through their chain – based suppliers. The production disruption has been immediate and devastating.

This disruption has upturned the key supply chain pillars of supply and demand management and is at a level beyond the previous contingency measures businesses have developed. Companies are now urgently focusing on better understanding their supply chains’ risk areas as they strive toward building more resilient and assured supply chains.

In the short term

When restating a business’s purpose, a good start is keeping front and center that the design of any supply chain starts with the end in mind and the nature of the markets to be serviced. The ability to set and deliver a repeatable service promise is the success measure. At its core ‘the promise’ consists of two elements ‘availability’ and ‘delivery’ with the third element ‘recovery’ being triggered as ‘necessary’.

This is taking the form of a reconfirmation of purpose as they undertake longer term restructures.

We define:

- Availability: Ensure Availability of the required products, in the right place at the right time

- Delivery: ensure the network structure and transport operating model is set up to achieve the required lead times

- Recovery: as acting quickly to respond to the effects of supply disruptions. This may include finding alternative suppliers, extending lead times, suspending or limiting new customer orders, renegotiating customer contracts

However, operational recovery alone does not provide for a long-term solution and indeed may not always be effective in terms of service or cost. This is where the fourth pillar ‘resilience’ comes into play

Supply Chain Resilience

A long-term strategy

Resilience is about developing strategic contingency plans. These plans would be identified through gaming potential scenarios and then used to develop effective countermeasures to mitigate the risks that can threaten your business.

Supply chain resilience as a concept is not new, with companies like Pepsi Co, and Procter & Gamble successfully implementing such strategies since 2012. Toyota has invested significantly in supply chain resilience by collaborating with its partners and creating supply chain maps that visualise the networks for each of its product components. If disaster strikes, the company can quickly identify which components are at risk and therefore trigger plans to reduce dependence on the impacted provider.

Even well-prepared companies can be at risk if they do not formulate a whole-of-network view. Recent events have led to the realisation that a resilience strategy that may be no different to your competitors may not afford the anticipated degree of protection. Indeed, this realisation may be the most important first step you can take on the journey to building supply chain resilience.

An Outline

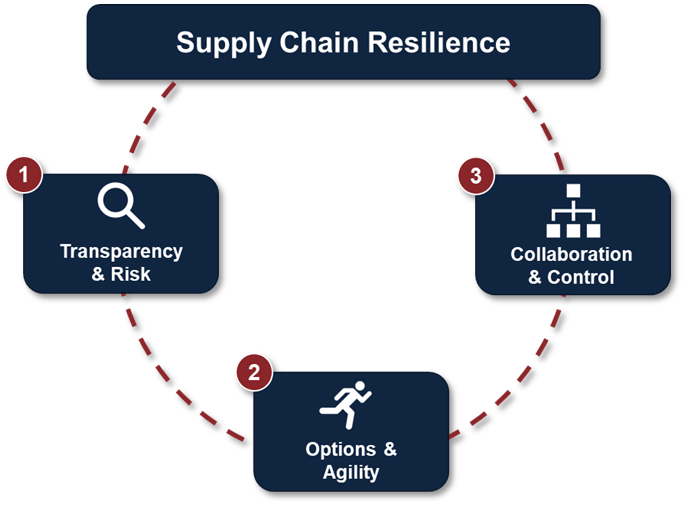

The Siecap view is that supply chain resilience is underpinned by three critical elements.

This is reinforced by a recent study by the Henry Jackson Society that identified that ‘Australia is strategically dependent on China across 595 categories of goods. This compares to the US at 414 and Britain at 229’.

1. Supply Chain Transparency & Risk

Supply chain transparency is considered the most important factor in achieving supply chain resilience. It is all too common that companies who sell finished goods only have information on production and shipment schedules relating to their Tier 1 suppliers. This leaves them significantly disadvantaged if the lower tier suppliers fail or the company losses access to them.

In an everchanging environment, supply chain transparency provides the required information about various entities including inventory, forecasting, logistics, transportation, and distribution. It elevates the understanding as to the risks posed to your supply chain. The benefits of achieving this supply chain transparency include:

- Performance and Compliance Improvement: greater visibility over your supply chain may help you identify opportunities to reduce lead time, boost efficiencies or reduce waste

- Risk Reduction: thorough understanding of your supply chain can help identify issues early so that action can be taken

- Quality control: Changes or improvements may add value to the end product or ensure it meets the standards expected.

To achieve visibility companies must:

- recognise the process of their supply chain;

- identify the primary functions of their supply chain;

- figure out the secondary and supporting functions of their supply chain;

- frame risks around key categories, products, geographies, jurisdictions and business models; and

- develop a mechanism to dynamically track and review flows and the risks associated with those flows.

Achieving supply chain transparency gives organisations the capability to identify areas of material, resource and reputational risk and avoid such traps as being complicit with supporting modern day slavery.

“Supply and demand disruption can come in many forms with the ‘lean’ supply chain highly exposed to risk”.

2. Options & Supply Chain Agility

Only once visibility and risks have been documented can options to mitigate supply shocks be developed for testing, evaluation and execution. What COVID-19 has demonstrated is that these options should consider key areas such as:

- supply diversification;

- investment in emerging providers;

- bringing back onshore critical functions; and

- investing in technology and analytics.

Traditional supply chain network flows and functional capability must be challenged through rigorous scenario testing. What this also means is the incorporation of cost-based risk overlays to ‘lean’ supply chain and ‘just-in-time’ inventory management solutions that have been exposed by the crisis.

Supply chain agility is about a company’s having the ability to thrive in a changing and unpredictable business environment. To achieve supply chain resilience, a company must develop a supply chain that incorporates networks capable of rapidly responding to changing conditions.

In order to achieve this, businesses must:

- identify or develop alternate suppliers and duel/multi-sourcing options;

- foster flexible manufacturing that can produce multiple products;

- adopt a more risk-based approach to holding and staging of inventory across the network;

- embrace technology in developing systems to capture events and respond swiftly; and

- build access to on-ground intelligence that can interpret events and initiate the appropriate response to unfolding situations.

Achieving supply chain agility allows companies to quickly minimise risk through the diversification of their supply base. Sectors such as pharmaceuticals or agricultural chemicals that rely heavily on raw material inputs from China immediately felt the impacts of COVID-19 supply disruption. Spreading raw ingredient production to other countries will successfully mitigate trade based risk exposure.

3. Supply Chain Collaboration & Control

By establishing collaborative partnerships, organisations can work together during catastrophe and mitigate risk. Organisations can achieve this by:

- enhanced integrated business planning, achieved by collaborative planning through all tiers of the supply chain to communicate more meaningful information more readily;

- matching customer demand and supplier capabilities through collaboration; and

- accessing supply chain demand, supply and inventory data and capacity constraints across the network.

If companies cannot sell inventory due to a global softening of demand, it will tie up working capital in holding and handling inventory. Through supply chain collaboration, companies can better understand inventory requirements through periods of prolonged product disruption. This will assist them to consider risks, not just costs.

Supply chain control is an organisation’s ability to change policies throughout the supply chain to react to changes in the market. By being able to execute change, companies can prevent disruption due to regulation, legal and social issues. In order to achieve this companies, need the ability to:

- develop products with appropriate levels of safety stock that is continually aligned to the realities of supply and demand;

- protect end-to-end product flow;

- establish adequate regulatory controls;

- develop key performance metrics, data capture and management systems to report on the attainment of the measures;

- Increase capability and control of internal processing and value add tasks through automation and high-tech manufacturing

The federal government has established the COVID-19 Coordination Commission to identify how business, including manufacturing, can thrive in a post-COVID-19 world.

Mr. Neville Power, the executive chairman of the National COVID-19 Co-ordination Commission, told Sky News “the sector must embrace high tech, flexible manufacturing that is modern and attracts a sort of investment we need. In the early days, post pandemic, we will have a low dollar, disrupted supply chains which create opportunities for local manufacturing.”

Summary

COVID-19 has been the black swan event that has shone a spotlight on the innate weakness contained within today’s offshore supply chains. This exposure should provide the impetus to apply an organisations energies to address these long-term structural weaknesses. By developing ‘resilience’ capability as opposed to ‘recovery’ skills, companies will no longer be corralled by the limitations of the trend to ultra-lean practices that have driven global supply design over the past two decades. Mapping supply chains, achieving visibility, costing, developing agile options and collaborating with others will allow organisations to ride out the shocks of the future.

Further Reading:

- Modern Day Slavery can have a direct effect on the resilience of your supply chain.

- Supply Chain Assurance requires detailed process mapping to create transparency.

Please contact us any time to arrange a no obligations meeting and understand how Siecap can add value to your organisation’s logistics and supply chain processes.